8 Representation Learning (Autoencoders)

In previous chapters, we have largely focused on classification and regression problems, where we use supervised learning with training samples that have both features/inputs and corresponding outputs or labels, to learn hypotheses or models that can then be used to predict labels for new data.

In contrast to supervised learning paradigm, we can also have an unsupervised learning setting, where we only have features but no corresponding outputs or labels for our dataset. A natural question arises then: if there are no labels, what are we learning?

One canonical example of unsupervised learning is clustering, which is discussed in Section 10.3. In clustering, the goal is to develop algorithms that can reason about “similarity” among data points’s features, and group the data points into clusters.

Autoencoders are another family of unsupervised learning algorithms, in this case seeking to obtain insights about our data by learning compressed versions of the original data, or, in other words, by finding a good lower-dimensional feature representations of the same data set. Such insights might help us to discover and characterize underlying factors of variation in data, which can aid in scientific discovery; to compress data for efficient storage or communication; or to pre-process our data prior to supervised learning, perhaps to reduce the amount of data that is needed to learn a good classifier or regressor.

8.1 Autoencoder structure

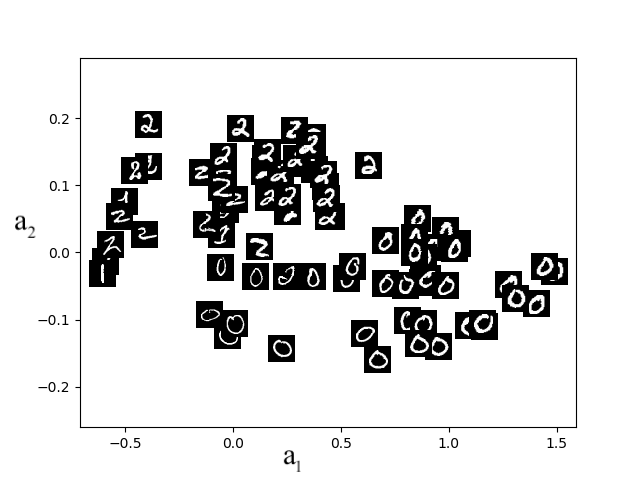

Assume that we have input data \(\mathcal{D} = \{x^{(1)}, \ldots, x^{(n)} \}\), where \(x^{(i)}\in \mathbb{R}^d\). We seek to learn an autoencoder that will output a new dataset \(\mathcal{D}_{out} = \{a^{(1)}, \ldots, a^{(n)}\}\), where \(a^{(i)}\in \mathbb{R}^k\) with \(k < d\). We can think about \(a^{(i)}\) as the new representation of data point \(x^{(i)}\). For example, in Figure 8.1 we show the learned representations of a dataset of MNIST digits with \(k=2\). We see, after inspecting the individual data points, that unsupervised learning has found a compressed (or latent) representation where images of the same digit are close to each other, potentially greatly aiding subsequent clustering or classification tasks.

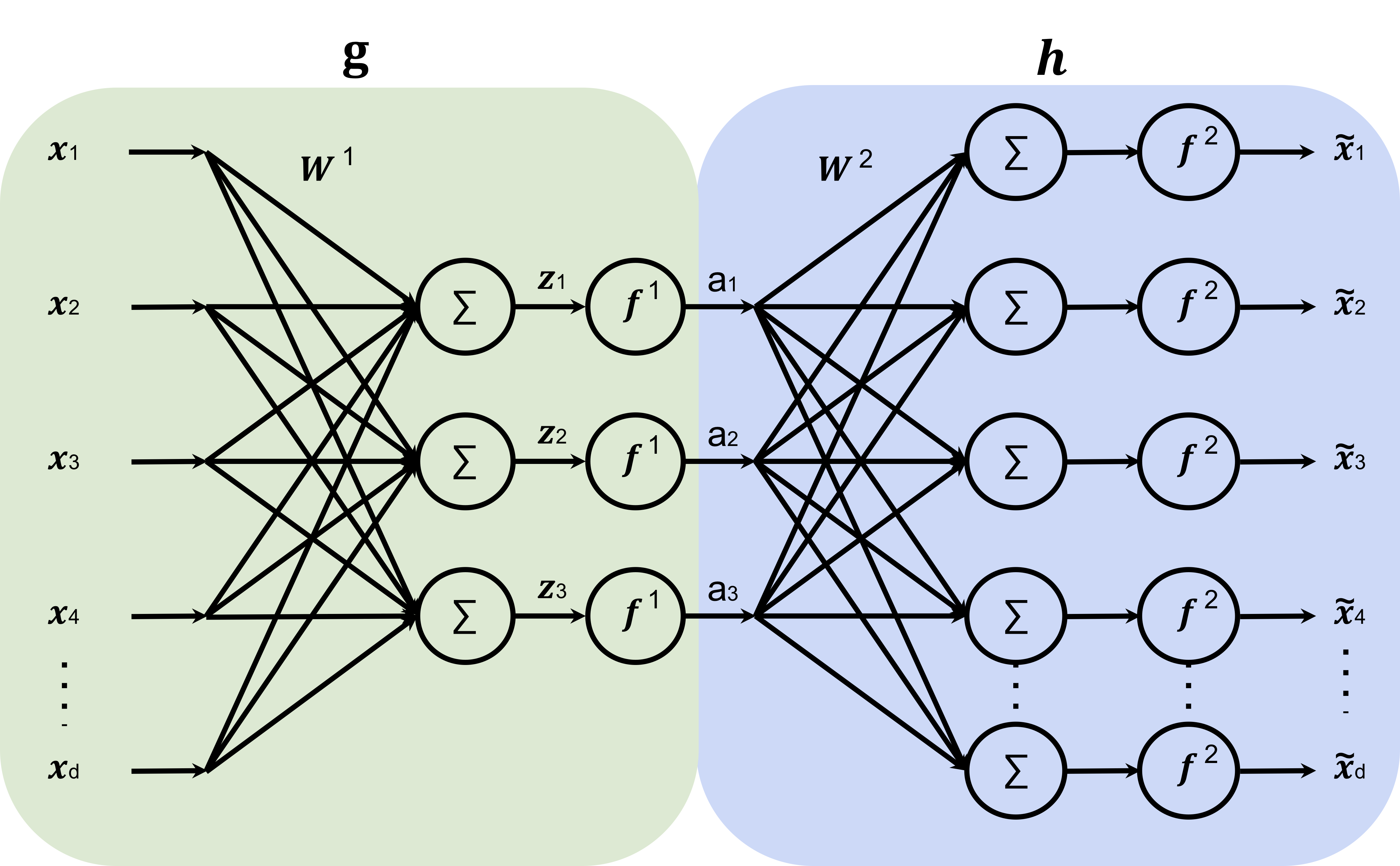

Formally, an autoencoder consists of two functions, a vector-valued encoder \(g : \mathbb{R}^d \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^k\) that deterministically maps the data to the representation space \(a \in \mathbb{R}^k\), and a decoder \(h : \mathbb{R}^k \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^d\) that maps the representation space back into the original data space.

In general, the encoder and decoder functions might be any functions appropriate to the domain. Here, we are particularly interested in neural network embodiments of encoders and decoders. The basic architecture of one such autoencoder, consisting of only a single layer neural network in each of the encoder and decoder, is shown in Figure 8.2; note that bias terms \(W^1_0\) and \(W^2_0\) into the summation nodes exist, but are omitted for clarity in the figure. In this example, the original \(d\)-dimensional input is compressed into \(k=3\) dimensions via the encoder \(g(x; W^1, W^1_0)=f_1(W{^1}^T x + W^1_0)\) with \(W^1 \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times k}\) and \(W^1_0 \in \mathbb{R}^k\), and where the non-linearity \(f_1\) is applied to each dimension of the vector. To recover (an approximation to) the original instance, we then apply the decoder \(h(a; W^2, W^2_0) = f_2(W{^2}^T a + W^2_0)\), where \(f_2\) denotes a different non-linearity (activation function). In general, both the decoder and the encoder could involve multiple layers, as opposed to the single layer shown here. Learning seeks parameters \(W^1, W^1_0\) and \(W^2, W^2_0\) such that the reconstructed instances, \(h(g(x^{(i)}; W^{1}, W^1_0); W^{2}, W^2_0)\), are close to the original input \(x^{(i)}\).

8.2 Autoencoder Learning

We learn the weights in an autoencoder using the same tools that we previously used for supervised learning, namely (stochastic) gradient descent of a multi-layer neural network to minimize a loss function. All that remains is to specify the loss function \(\mathcal{L}(\tilde{x}, x)\), which tells us how to measure the discrepancy between the reconstruction \(\tilde{x} = h(g(x; W^{1}, W^1_0); W^{2}, W^2_0)\) and the original input \(x\). For example, for continuous-valued \(x\) it might make sense to use squared loss, i.e., \(\mathcal{L}_{SE}(\tilde{x}, x) = \sum_{j=1}^{d} (x_j - \tilde{x}_j)^2\).

Alternatively, you could think of this as multi-task learning, where the goal is to predict each dimension of \(x\). One can mix-and-match loss functions as appropriate for each dimension’s data type.

Learning then seeks to optimize the parameters of \(h\) and \(g\) so as to minimize the reconstruction error, measured according to this loss function: \[\min_{W^{1}, W^1_0, W^{2}, W^2_0} \sum_{i=1}^n \mathcal{L}_{SE}\left(h(g(x^{(i)}; W^{1}, W^1_0); W^{2}, W^2_0), x^{(i)}\right)\]

8.3 Evaluating an autoencoder

What makes a good learned representation in an autoencoder? Notice that, without further constraints, it is always possible to perfectly reconstruct the input. For example, we could let \(k=d\) and \(h\) and \(g\) be the identity functions. In this case, we would not obtain any compression of the data.

To learn something useful, we must create a bottleneck by making \(k\) to be smaller (often much smaller) than \(d\). This forces the learning algorithm to seek transformations that describe the original data using as simple a description as possible. Thinking back to the digits dataset, for example, an example of a compressed representation might be the digit label (i.e., 0–9), rotation, and stroke thickness. Of course, there is no guarantee that the learning algorithm will discover precisely this representation. After learning, we can inspect the learned representations, such as by artificially increasing or decreasing one of the dimensions (e.g., \(a_1\)) and seeing how it affects the output \(h(a)\), to try to better understand what it has learned.

As with clustering, autoencoders can be a preliminary step toward building other models, such as a regressor or classifier. For example, once a good encoder has been learned, the decoder might be replaced with another neural network that is then trained with supervised learning (perhaps using a smaller dataset that does include labels).

8.4 Linear encoders and decoders

We close by mentioning that even linear encoders and decoders can be very powerful. In this case, rather than minimizing the above objective with gradient descent, a technique called principal components analysis (PCA) can be used to obtain a closed-form solution to the optimization problem using a singular value decomposition (SVD). Just as a multilayer neural network with nonlinear activations for regression (learned by gradient descent) can be thought of as a nonlinear generalization of a linear regressor (fit by matrix algebraic operations), the neural network based autoencoders discussed above (and learned with gradient descent) can be thought of as a generalization of linear PCA (as solved with matrix algebra by SVD).

8.5 Advanced encoders and decoders

Advanced neural networks built on encoder-decoder architectures have become increasingly powerful. One prominent example is generative networks, designed to create new outputs that resemble—but differ from—existing training examples. A notable type, variational autoencoders, learns a compressed representation capturing statistical properties (such as mean and variance) of training data. These latent representations can then be sampled to generate novel outputs using the decoder.

Another influential encoder-decoder architecture is the Transformer, covered in Chapter 9. Transformers consist of multiple encoder and decoder layers combined with self-attention mechanisms, which excel at predicting sequential data, such as words and sentences in natural language processing (NLP).

Central to autoencoders and Transformers is the idea of learning representations. Autoencoders compress data into efficient, informative representations, while NLP models encode language—words, phrases, sentences—into numerical forms. This numerical encoding leads us to the concept of vector embeddings.

8.6 Embeddings

In NLP, words are represented as vectors, commonly known as word embeddings. A key property of good embeddings is that their numerical closeness mirrors semantic similarity. For instance, semantically related words such as “dog” and “cat” should have vectors close together, while unrelated words like “cat” and “table” should be farther apart.

Similarity between embeddings is frequently measured using the inner product:

\[a^T b = a \cdot b\]

The inner product indicates how aligned two vectors are: highly positive values imply strong similarity, negative values indicate opposition, and values near zero suggest no similarity (up to a scaling factor related to the magnitude).

A groundbreaking embedding method, word2vec (2012), significantly advanced NLP by producing embeddings where vector arithmetic corresponded to real-world semantic relationships. For instance:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{embedding}_{\tt paris} - \text{embedding}_{\tt france} + \text{embedding}_{\tt italy} \approx \text{embedding}_{\tt rome} \end{aligned}\]

Such embeddings revealed meaningful semantic relationships like analogies across diverse vocabulary (e.g., uncle – man + woman ≈ aunt).

Importantly, embeddings don’t need exact coordinates—it’s their relative positioning within the vector space that matters. Embeddings are considered effective if they facilitate downstream NLP tasks, such as predicting missing words, classifying texts, or language translation.

For example, effective embeddings allow models to accurately predict a missing word in a sentence:

After the rain, the grass was ____.

Or a model could be built that tries to correctly predict words in the middle of sentences:

The child fell __ __ during the long car ride

This task exemplifies self-supervision, a training approach where models generate labels directly from the data itself, eliminating the need for manual labeling. Training neural networks through self-supervision involves optimizing their ability to predict words accurately from large text corpora (e.g., Wikipedia). Through such optimization, embeddings capture subtle semantic and syntactic nuances, greatly enhancing NLP capabilities.

The idea of good embeddings will play a central role when we discuss attention mechanisms in Chapter 9, where embeddings dynamically adjust based on context (via the so-called attention mechanism), enabling a more nuanced understanding of language.