10 Non-parametric Models

Neural networks have adaptable complexity, in the sense that we can try different structural models and use cross validation to find one that works well on our data. Beyond neural networks, we may further broaden the class of models that we can fit to our data, for example as illustrated by the techniques introduced in this chapter.

Here, we turn to models that automatically adapt their complexity to the training data. The name non-parametric methods is misleading: it is really a class of methods that does not have a fixed parameterization in advance. Rather, the complexity of the parameterization can grow as we acquire more data.

Some non-parametric models, such as nearest-neighbor, rely directly on the data to make predictions and do not compute a model that summarizes the data. Other non-parametric methods, such as decision trees, can be seen as dynamically constructing something that ends up looking like a more traditional parametric model, but where the actual training data affects exactly what the form of the model will be.

The non-parametric methods we consider here tend to have the form of a composition of simple models:

Nearest neighbor models: Section 10.1 where we don’t process data at training time, but do all the work when making predictions, by looking for the closest training example(s) to a given new data point.

Tree models: Section 10.2 where we partition the input space and use different simple predictions on different regions of the space; the hypothesis space can become arbitrarily large allowing finer and finer partitions of the input space.

Ensemble models: Section 10.2.3 in which we train several different classifiers on the whole space and average the answers; this decreases the estimation error. In particular, we will look at bootstrap aggregation, or bagging of trees.

Boosting is a way to construct a model composed of a sequence of component models (e.g., a model consisting of a sequence of trees, each subsequent tree seeking to correct errors in the previous trees) that decreases both estimation and structural error. We won’t consider this in detail in this class.

*\(k\)-means clustering methods, Section 10.3 where we partition data into groups based on similarity without predefined labels, adapting complexity by adjusting the number of clusters.

Why are we studying these methods, in the heyday of complicated models such as neural networks ?

They are fast to implement and have few or no hyperparameters to tune.

They often work as well as or better than more complicated methods.

Predictions from some of these models can be easier to explain to a human user: decision trees are fairly directly human-interpretable, and nearest neighbor methods can justify their decisions to some extent by showing a few training examples that the predictions were based on.

10.1 Nearest Neighbor

In nearest-neighbor models, we don’t do any processing of the data at training time – we just remember it! All the work is done at prediction time.

Input values \(x\) can be from any domain \(\mathcal X\) (\(\mathbb{R}^d\), documents, tree-structured objects, etc.). We just need a distance metric, \(d: \mathcal X \times \mathcal X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+\), which satisfies the following, for all \(x, x', x'' \in \mathcal X\): \[\begin{aligned} d(x, x) & = 0 \\ d(x, x') & = d(x', x) \\ d(x, x'') & \leq d(x, x') + d(x', x'') \end{aligned}\]

Given a data-set \({\cal D}= \{(x^{(i)},y^{(i)})\}_{i=1}^n\), our predictor for a new \(x \in \mathcal X\) is \[h(x) = y^{(i)} \;\;\;\text{where}\;\;\;i = {\rm arg}\min_{i} d(x, x^{(i)})\;\;,\] that is, the predicted output associated with the training point that is closest to the query point \(x\). Tie breaking is typically done at random.

This same algorithm works for regression and classification!

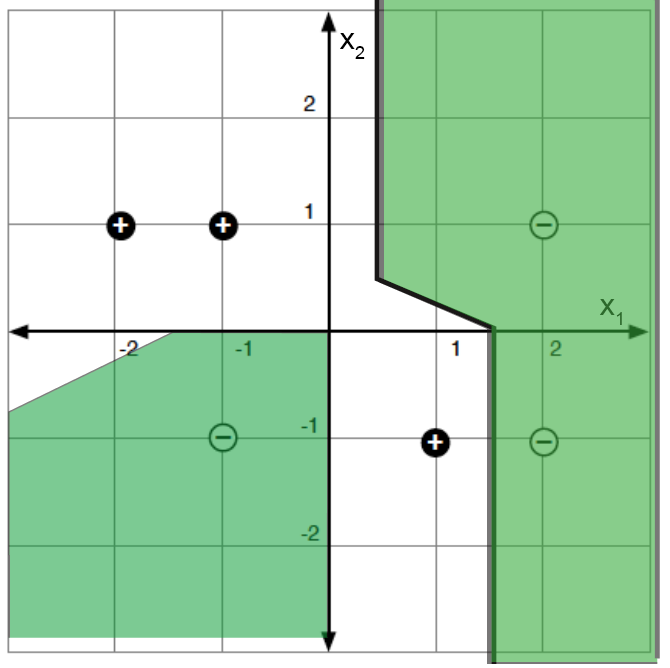

The nearest neighbor prediction function can be described by dividing the space up into regions whose closest point is each individual training point as shown below:

In each region, we predict the associated \(y\) value.

There are several useful variations on this method. In \(k\)-nearest-neighbors, we find the \(k\) training points nearest to the query point \(x\) and output the majority \(y\) value for classification or the average for regression. We can also do locally weighted regression in which we fit locally linear regression models to the \(k\) nearest points, possibly giving less weight to those that are farther away. In large data-sets, it is important to use good data structures (e.g., ball trees) to perform the nearest-neighbor look-ups efficiently (without looking at all the data points each time).

10.2 Tree Models

The idea here is that we would like to find a partition of the input space and then fit very simple models to predict the output in each piece. The partition is described using a (typically binary) “tree” that recursively splits the space.

Tree methods differ by:

The class of possible ways to split the space at each node; these are typically linear splits, either aligned with the axes of the space, or sometimes using more general classifiers.

The class of predictors within the partitions; these are often simply constants, but may be more general classification or regression models.

The way in which we control the complexity of the hypothesis: it would be within the capacity of these methods to have a separate partition element for each individual training example.

The algorithm for making the partitions and fitting the models.

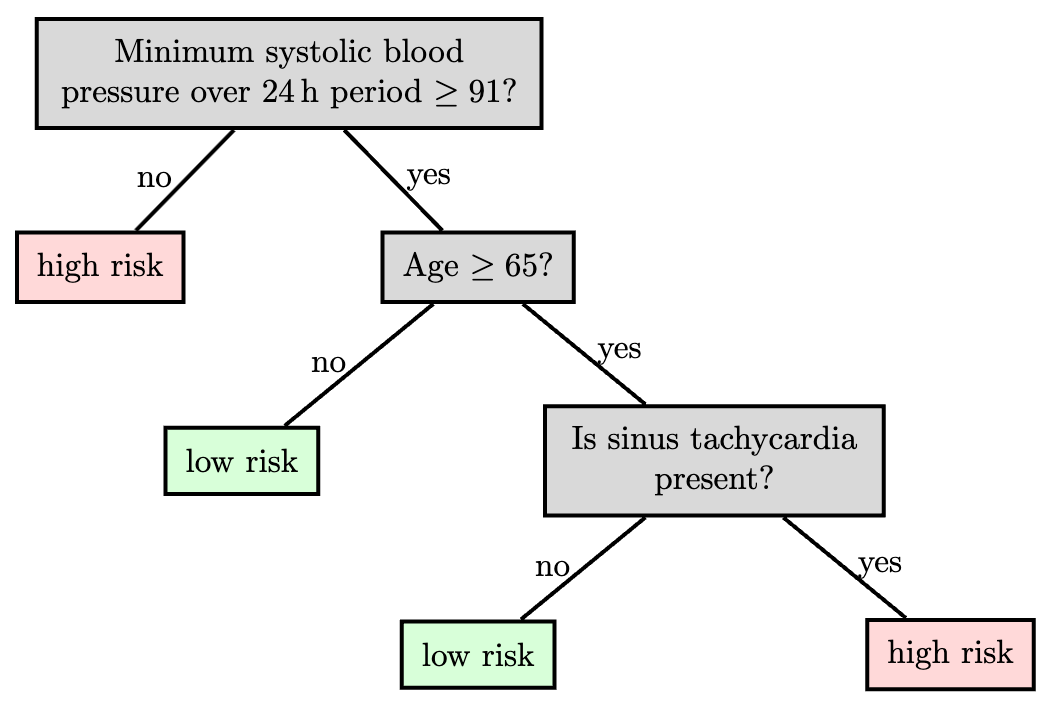

One advantage of tree models is that they are easily interpretable by humans. This is important in application domains, such as medicine, where there are human experts who often ultimately make critical decisions and who need to feel confident in their understanding of recommendations made by an algorithm. Below is an example decision tree, illustrating how one might be able to understand the decisions made by the tree.

These methods are most appropriate for domains where the input space is not very high-dimensional and where the individual input features have some substantially useful information individually or in small groups. Trees would not be good for image input, but might be good in cases with, for example, a set of meaningful measurements of the condition of a patient in the hospital, as in the example above.

We’ll concentrate on the CART/ID3 (“classification and regression trees” and “iterative dichotomizer 3”, respectively) family of algorithms, which were invented independently in the statistics and the artificial intelligence communities. They work by greedily constructing a partition, where the splits are axis aligned and by fitting a constant model in the leaves. The interesting questions are how to select the splits and how to control complexity. The regression and classification versions are very similar.

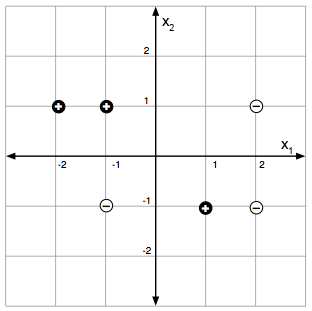

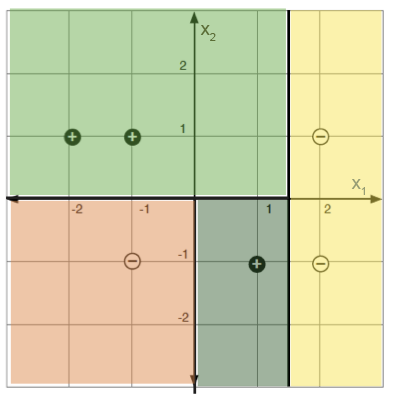

As a concrete example, consider the following images:

The left image depicts a set of labeled data points in a two-dimensional feature space. The right shows a partition into regions by a decision tree, in this case having no classification errors in the final partitions.

10.2.1 Regression

The predictor is made up of

a partition function, \(\pi\), mapping elements of the input space into exactly one of \(M\) regions, \(R_1, \ldots, R_M\), and

a collection of \(M\) output values, \(O_m\), one for each region.

If we already knew a division of the space into regions, we would set \(O_m\), the constant output for region \(R_m\), to be the average of the training output values in that region. For a training data set \({\cal D}= \left\{\left(x^{(i)}, y^{(i)}\right)\right\}, i = 1, \ldots n\), we let \(I\) be an indicator set of all of the elements within \({\cal D}\), so that \(I = \{1, \ldots, n\}\) for our whole data set. We can define \(I_m\) as the subset of data set samples that are in region \(R_m\), so that \(I_m = \{ i \mid x^{(i)} \in R_m\}\). Then \[O_m = {\rm average}_{i \in I_m}~y^{(i)}\;\;.\] We can define the error in a region as \(E_m\). For example, \(E_m\) as the sum of squared error would be expressed as \[E_m = \sum_{i \in I_m}(y^{(i)} - O_m)^2\;\;.\] Ideally, we should select the partition to minimize \[\lambda M + \sum_{m=1}^M E_m\;\;,\] for some regularization constant \(\lambda\). It is enough to search over all partitions of the training data (not all partitions of the input space!) to optimize this, but the problem is NP-complete.

10.2.1.1 Building a tree

So, we’ll be greedy. We establish a criterion, given a set of data, for finding the best single split of that data, and then apply it recursively to partition the space. For the discussion below, we will select the partition of the data that minimizes the sum of the sum of squared errors of each partition element. Then later, we will consider other splitting criteria.

Given a data set \({\cal D}= \left\{\left(x^{(i)}, y^{(i)}\right)\right\}, i = 1, \ldots n\), we now consider \(I\) to be an indicator of the subset of elements within \({\cal D}\) that we wish to build a tree (or subtree) for. That is, \(I\) may already indicate a subset of data set \({\cal D}\), based on prior splits in constructing our overall tree. We define terms as follows:

\(I^+_{j,s}\) indicates the set of examples (subset of \(I\)) whose feature value in dimension \(j\) is greater than or equal to split point \(s\);

\(I^-_{j,s}\) indicates the set of examples (subset of \(I\)) whose feature value in dimension \(j\) is less than \(s\);

\(\hat{y}^+_{j,s}\) is the average \(y\) value of the data points indicated by set \(I^+_{j,s}\); and

\(\hat{y}^-_{j,s}\) is the average \(y\) value of the data points indicated by set \(I^-_{j,s}\).

Here is the pseudocode. In what follows, \(k\) is the largest leaf size that we will allow in the tree, and is a hyperparameter of the algorithm.

In practice, we typically start by calling BuildTree with the first input equal to our whole data set (that is, with \(I = \{1,\ldots,n\}\)). But then that call of BuildTree can recursively lead to many other calls of BuildTree.

Let’s think about how long each call of BuildTree takes to run. We have to consider all possible splits. So we consider a split in each of the \(d\) dimensions. In each dimension, we only need to consider splits between two data points (any other split will give the same error on the training data). So, in total, we consider \(O(d n)\) splits in each call to BuildTree.

10.2.1.2 Pruning

It might be tempting to regularize by using a somewhat large value of \(k\), or by stopping when splitting a node does not significantly decrease the error. One problem with short-sighted stopping criteria is that they might not see the value of a split that will require one more split before it seems useful. So, we will tend to build a tree that is too large, and then prune it back.

We define cost complexity of a tree \(T\), where \(m\) ranges over its leaves, as \[C_\alpha(T) = \sum_{m = 1}^{|T|} E_m(T) + \alpha |T|\;\;,\] and \(|T|\) is the number of leaves. For a fixed \(\alpha\), we can find a \(T\) that (approximately) minimizes \(C_\alpha(T)\) by “weakest-link” pruning:

Create a sequence of trees by successively removing the bottom-level split that minimizes the increase in overall error, until the root is reached.

Return the \(T\) in the sequence that minimizes the cost complexity.

We can choose an appropriate \(\alpha\) using cross validation.

10.2.2 Classification

The strategy for building and pruning classification trees is very similar to the strategy for regression trees.

Given a region \(R_m\) corresponding to a leaf of the tree, we would pick the output class \(y\) to be the value that exists most frequently (the majority value) in the data points whose \(x\) values are in that region, i.e., data points indicated by \(I_m\): \[O_m = {\rm majority}_{i \in I_m}~y^{(i)}\;\;.\] Let’s now define the error in a region as the number of data points that do not have the value \(O_m\): \[E_m = \left|\{i \mid i \in I_m \;\text{and}\; y^{(i)} \not = O_m\}\right|\;\;.\] We define the empirical probability of an item from class \(k\) occurring in region \(m\) as: \[\hat{P}_{m,k} = \hat{P}(I_m,k) = \frac{\left|\{i \mid i \in I_m \;\text{and}\; y^{(i)} = k\}\right|}{N_m}\;\;,\] where \(N_m\) is the number of training points in region \(m\); that is, \(N_m = |I_m|.\) For later use, we’ll also define the empirical probabilities of split values, \(\hat{P}_{m,j,s}\), as the fraction of points with dimension \(j\) in split \(s\) occurring in region \(m\) (one branch of the tree), and \(1 - \hat{P}_{m,j,s}\) as the complement (the fraction of points in the other branch).

Splitting criteria

In our greedy algorithm, we need a way to decide which split to make next. There are many criteria that express some measure of the “impurity” in child nodes. Some measures include:

Misclassification error: \[Q_m(T) = \frac{E_m}{N_m} = 1 - \hat{P}_{m,O_m}\]

Gini index: \[Q_m(T) = \sum_k \hat{P}_{m,k}(1 - \hat{P}_{m,k})\]

Entropy: \[Q_m(T) = H(I_m) = - \sum_k \hat{P}_{m,k} \log_2 \hat{P}_{m,k}\] So that the entropy \(H\) is well-defined when \(\hat{P} = 0\), we will stipulate that \(0 \log_2 0 = 0\).

These splitting criteria are very similar, and it’s not entirely obvious which one is better. We will focus on entropy, just to be concrete.

Analogous to how for regression we choose the dimension \(j\) and split \(s\) that minimizes the sum of squared error \(E_{j,s}\), for classification, we choose the dimension \(j\) and split \(s\) that minimizes the weighted average entropy over the “child” data points in each of the two corresponding splits, \(I^+_{j,s}\) and \(I^-_{j,s}\). We calculate the entropy in each split based on the empirical probabilities of class memberships in the split, and then calculate the weighted average entropy \(\hat{H}\) as \[\begin{aligned} \hat{H} & = \text{(fraction of points in left data set)} \cdot H(I_{j,s}^-) \nonumber \\ & \qquad + \text{(fraction of points in right data set)} \cdot H(I_{j,s}^+) \nonumber \\ & = (1-\hat{P}_{m,j,s}) H(I_{j,s}^-) + \hat{P}_{m,j,s} H(I_{j,s}^+) \nonumber \\ & = \frac{|I^-_{j,s}|}{N_m} \cdot H(I_{j,s}^-) + \frac{|I^+_{j,s}|}{N_m} \cdot H(I_{j,s}^+)\; . \end{aligned}\]

Choosing the split that minimizes the entropy of the children is equivalent to maximizing the information gain of the test \(x_j = s\), defined by \[\begin{aligned} \text{infoGain}(x_j = s, I_m) & = & H(I_m) - \left(\frac{|I^-_{j,s}|}{N_m} \cdot H(I_{j,s}^-) + \frac{|I^+_{j,s}|}{N_m} \cdot H(I_{j,s}^+)\right) \end{aligned}\]

In the two-class case (with labels 0 and 1), all of the splitting criteria mentioned above have the values \[\begin{cases} 0.0 & \text{when $\hat{P}_{m,0} = 0.0$} \\ 0.0 & \text{when $\hat{P}_{m,0} = 1.0$} \end{cases} \; .\] The respective impurity curves are shown below, where \(p = \hat{P}_{m,0}\); the vertical axis plots \(Q_m(T)\) for each of the three criteria.

There used to be endless haggling about which impurity function one should use. It seems to be traditional to use entropy to select which node to split while growing the tree, and misclassification error in the pruning criterion.

10.2.3 Bagging

One important limitation or drawback in conventional trees is that they can have high estimation error: small changes in the data can result in very big changes in the resulting tree.

Bootstrap aggregation is a technique for reducing the estimation error of a non-linear predictor, or one that is adaptive to the data. The key idea applied to trees, is to build multiple trees with different subsets of the data, and then create an ensemble model that combines the results from multiple trees to make a prediction.

Construct \(B\) new data sets of size \(n\). Each data set is constructed by sampling \(n\) data points with replacement from \({\cal D}\). A single data set is called bootstrap sample of \({\cal D}\).

Train a predictor \(\hat{f}^b(x)\) on each bootstrap sample. When building each tree, the standard tree-building algorithm is used, which considers all features when deciding how to split at each node.

Regression case: bagged predictor is \[\hat{f}_{\rm bag}(x) = \frac{1}{B} \sum_{b=1}^B \hat{f}^b(x) \; .\]

Classification case: Let \(K\) be the number of classes. We find a majority bagged predictor as follows. We let \(\hat{f}^b(x)\) be a “one-hot” vector with a single 1 and \(K-1\) zeros, and define the predicted output \(\hat{y}\) for predictor \(f^b\) as \(\hat{y}^b(x) = {\rm arg}\max_{k} \hat{f}^b(x)_k\). Then \[\hat{f}_{\rm bag}(x) = \frac{1}{B} \sum_{b=1}^B \hat{f}^b(x),\] which is a vector containing the proportion of classifiers that predicted each class \(k\) for input \(x.\) Then the overall predicted output is \[\hat{y}_{\rm bag}(x) = {\rm arg}\max_{k} \hat{f}_{\rm bag}(x)_k\;\;.\]

There are theoretical arguments showing that bagging does, in fact, reduce estimation error. However, when we bag a model, any simple intrepetability is lost.

10.2.4 Random Forests

Random forests extend bagging by introducing an additional source of randomness during tree construction. While bagging uses bootstrap sampling to create diversity across trees, random forests also add random feature selection at each split. This additional randomization helps de-correlate the trees, so that using them to vote gives maximal advantage. In competitions, they often have excellent classification performance among large collections of much fancier methods.

The key difference from bagging is that when building each tree, at each split node, rather than considering all \(d\) features to find the best split, random forests randomly select only \(m\) features (where \(m \leq d\) is a hyperparameter) and then choose the best split among those \(m\) features. This forces trees to be more diverse and less correlated with each other.

In what follows, \(B\), \(m\), and \(n\) are hyperparameters of the algorithm.

Given the ensemble of trees, vote to make a prediction on a new \(x\).

10.2.5 Tree variants and tradeoffs

There are many variations on the tree theme. One is to employ different regression or classification methods in each leaf. For example, a linear regression might be used to model the examples in each leaf, rather than using a constant value.

In the relatively simple trees that we’ve considered, splits have been based on only a single feature at a time, and with the resulting splits being axis-parallel. Other methods for splitting are possible, including consideration of multiple features and linear classifiers based on those, potentially resulting in non-axis-parallel splits. Complexity is a concern in such cases, as many possible combinations of features may need to be considered, to select the best variable combination (rather than a single split variable).

Another generalization is a hierarchical mixture of experts, where we make a “soft” version of trees, in which the splits are probabilistic (so every point has some degree of membership in every leaf). Such trees can be trained using a form of gradient descent. Combinations of bagging, boosting, and mixture tree approaches (e.g., gradient boosted trees) and implementations are readily available (e.g., XGBoost).

Trees have a number of strengths, and remain a valuable tool in the machine learning toolkit. Some benefits include being relatively easy to interpret, fast to train, and ability to handle multi-class classification in a natural way. Trees can easily handle different loss functions; one just needs to change the predictor and loss being applied in the leaves. Methods also exist to identify which features are particularly important or influential in forming the tree, which can aid in human understanding of the data set. Finally, in many situations, trees perform surprisingly well, often comparable to more complicated regression or classification models. Indeed, in some settings it is considered good practice to start with trees (especially random forest or boosted trees) as a “baseline” machine learning model, against which one can evaluate performance of more sophisticated models.

While tree-based methods excel at supervised learning tasks, we now turn to another important class of non-parametric methods that focus on discovering structure in unlabeled data. These clustering methods share some conceptual similarities with tree-based approaches - both aim to partition the input space into meaningful regions - but clustering methods operate without supervision, making them particularly valuable for exploratory data analysis and pattern discovery.

10.3 \(k\)-means Clustering

Clustering is an unsupervised learning method where we aim to discover meaningful groupings or categories in a dataset based on patterns or similarities within the data itself, without relying on pre-assigned labels. It is widely used for exploratory data analysis, pattern recognition, and segmentation tasks, allowing us to interpret and manage complex datasets by uncovering hidden structures and relationships.

Oftentimes a dataset can be partitioned into different categories. A doctor may notice that their patients come in cohorts and different cohorts respond to different treatments. A biologist may gain insight by identifying that bats and whales, despite outward appearances, have some underlying similarity, and both should be considered members of the same category, i.e., “mammal”. The problem of automatically identifying meaningful groupings in datasets is called clustering. Once these groupings are found, they can be leveraged toward interpreting the data and making optimal decisions for each group.

10.3.1 Clustering formalisms

Mathematically, clustering looks a bit like classification: we wish to find a mapping from datapoints, \(x\), to categories, \(y\). However, rather than the categories being predefined labels, the categories in clustering are automatically discovered partitions of an unlabeled dataset.

Because clustering does not learn from labeled examples, it is an example of an unsupervised learning algorithm. Instead of mimicking the mapping implicit in supervised training pairs \(\{x^{(i)},y^{(i)}\}_{i=1}^n\), clustering assigns datapoints to categories based on how the unlabeled data \(\{x^{(i)}\}_{i=1}^n\) is distributed in data space.

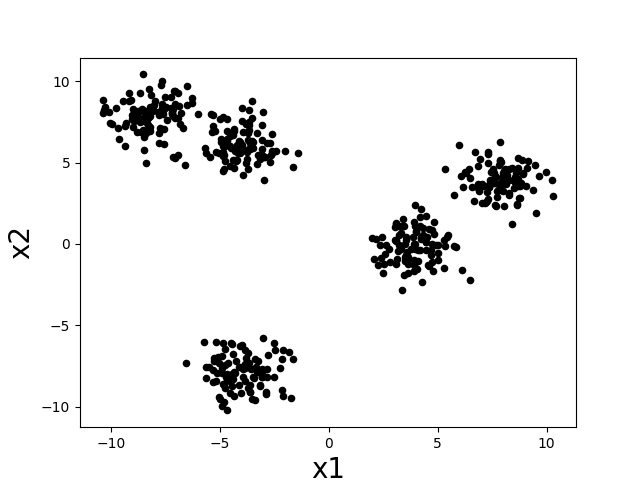

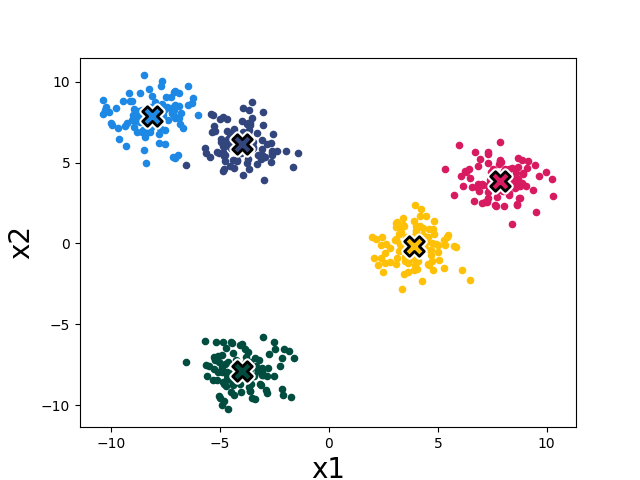

Intuitively, a “cluster” is a group of datapoints that are all nearby to each other and far away from other clusters. Let’s consider the following scatter plot. How many clusters do you think there are?

There seem to be about five clumps of datapoints and those clumps are what we would like to call clusters. If we assign all datapoints in each clump to a cluster corresponding to that clump, then we might desire that nearby datapoints are assigned to the same cluster, while far apart datapoints are assigned to different clusters.

In designing clustering algorithms, three critical things we need to decide are:

How do we measure distance between datapoints? What counts as “nearby” and “far apart”?

How many clusters should we look for?

How do we evaluate how good a clustering is?

We will see how to begin making these decisions as we work through a concrete clustering algorithm in the next section.

10.3.2 The k-means formulation

One of the simplest and most commonly used clustering algorithms is called k-means. The goal of the k-means algorithm is to assign datapoints to \(k\) clusters in such a way that the variance within clusters is as small as possible. Notice that this matches our intuitive idea that a cluster should be a tightly packed set of datapoints.

Similar to the way we showed that supervised learning could be formalized mathematically as the minimization of an objective function (loss function + regularization), we will show how unsupervised learning can also be formalized as minimizing an objective function. Let us denote the cluster assignment for a datapoint \(x^{(i)}\) as \(y^{(i)} \in \{1,2,\ldots,k\}\), i.e., \(y^{(i)} = 1\) means we are assigning datapoint \(x^{(i)}\) to cluster number 1. Then the k-means objective can be quantified with the following objective function (which we also call the “k-means loss”):

\[\sum_{j=1}^k \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbb{1}(y^{(i)} = j) \left\Vert x^{(i)} - \mu^{(j)} \right\Vert^2 \;, \tag{10.1}\]

where \(\mu^{(j)} = \frac{1}{N_j} \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbb{1}(y^{(i)} = j) x^{(i)}\) and \(N_j = \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbb{1}(y^{(i)} = j)\), so that \(\mu^{(j)}\) is the mean of all datapoints in cluster \(j\), and using \(\mathbb{1}(\cdot)\) to denote the indicator function (which takes on value of 1 if its argument is true and 0 otherwise). The inner sum (over data points) of the loss is the variance of datapoints within cluster \(j\). We sum up the variance of all \(k\) clusters to get our overall loss.

10.3.2.0.0.1 K-means algorithm

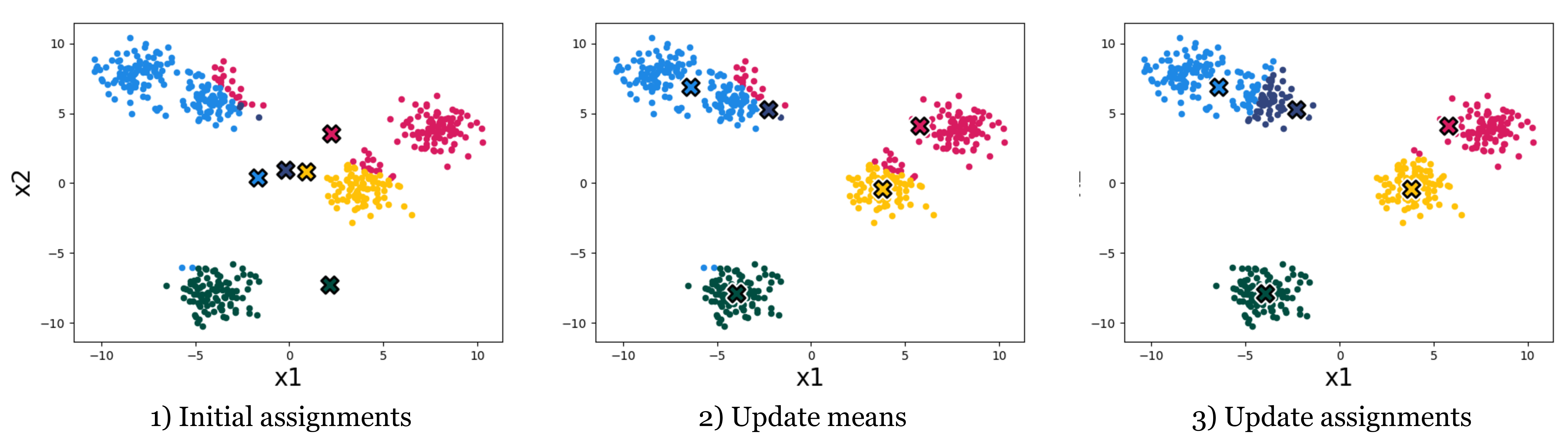

The k-means algorithm minimizes this loss by alternating between two steps: given some initial cluster assignments: 1) compute the mean of all data in each cluster and assign this as the “cluster mean”, and 2) reassign each datapoint to the cluster with nearest cluster mean. Figure 10.2 shows what happens when we repeat these steps on the dataset from above.

Each time we reassign the data to the nearest cluster mean, the k-means loss decreases (the datapoints end up closer to their assigned cluster mean), or stays the same. And each time we recompute the cluster means the loss also decreases (the means end up closer to their assigned datapoints) or stays the same. Overall then, the clustering gets better and better, according to our objective – until it stops improving.

After four iterations of cluster assignment + update means in our example, the k-means algorithm stops improving. We say it has converged, and its final solution is shown in Figure 10.3.

It seems to converge to something reasonable! Now let’s write out the algorithm in complete detail:

The for-loop over the \(n\) datapoints assigns each datapoint to the nearest cluster center. The for-loop over the k clusters updates the cluster center to be the mean of all datapoints currently assigned to that cluster. As suggested above, it can be shown that this algorithm reduces the loss in Equation 10.1 on each iteration, until it converges to a local minimum of the loss.

It’s like classification except it picked what the classes are rather than being given examples of what the classes are.

10.3.2.0.0.2 Using gradient descent to minimize k-means objective

We can also use gradient descent to optimize the k-means objective. To show how to apply gradient descent, we first rewrite the objective as a differentiable function only of \(\mu\): \[L(\mu) = \sum_{i=1}^n \min_j \left\Vert x^{(i)} - \mu^{(j)} \right\Vert^2 \;\;.\] \(L(\mu)\) is the value of the k-means loss given that we pick the optimal assignments of the datapoints to cluster means (that’s what the \(\min_j\) does). Now we can use the gradient \(\frac{\partial L(\mu)}{\partial \mu}\) to find the values for \(\mu\) that achieve minimum loss when cluster assignments are optimal. Finally, we read off the optimal cluster assignments, given the optimized \(\mu\), just by assigning datapoints to their nearest cluster mean: \[y^{(i)} = \arg\min_j \left\Vert x^{(i)} - \mu^{(j)} \right\Vert^2 \;\;.\] This procedure yields a local minimum of Equation 10.1, as does the standard k-means algorithm we presented (though they might arrive at different solutions). It might not be the global optimum since the objective is not convex (due to \(\min_j\), as the minimum of multiple convex functions is not necessarily convex).

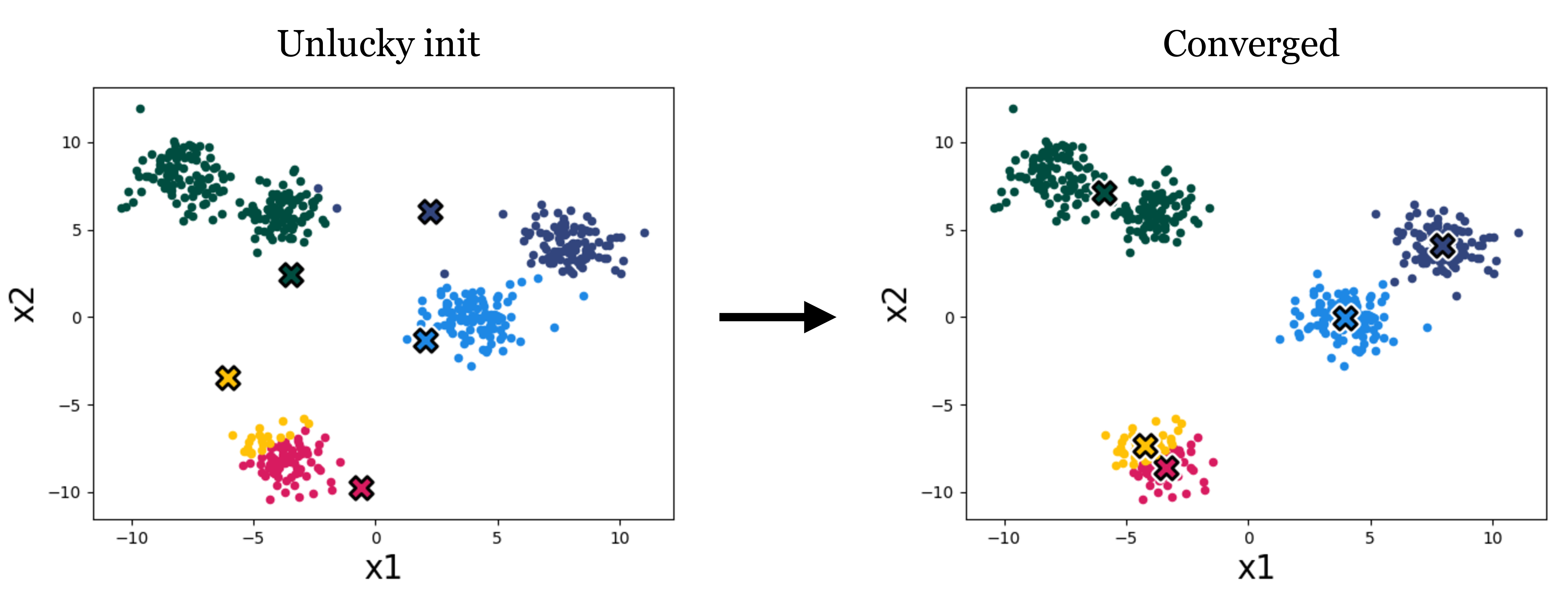

10.3.2.0.0.3 Importance of initialization

The standard k-means algorithm, as well as the variant that uses gradient descent, both are only guaranteed to converge to a local minimum, not necessarily the global minimum of the loss. Thus the answer we get out depends on how we initialize the cluster means. Figure 10.4 is an example of a different initialization on our toy data, which results in a worse converged clustering:

A variety of methods have been developed to pick good initializations (see, for example, the k-means++ algorithm). One simple option is to run the standard k-means algorithm multiple times, with different random initial conditions, and then pick from these the clustering that achieves the lowest k-means loss.

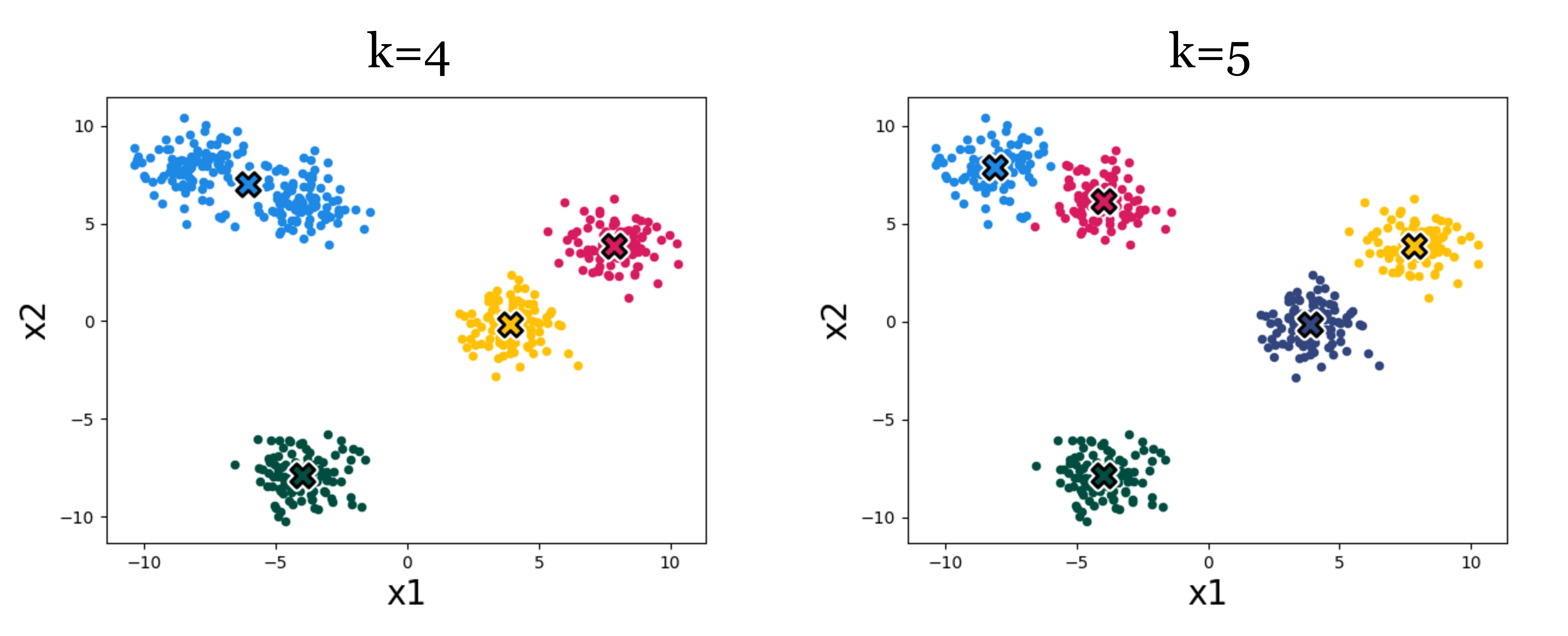

10.3.2.0.0.4 Importance of k

A very important parameter in cluster algorithms is the number of clusters we are looking for. Some advanced algorithms can automatically infer a suitable number of clusters, but most of the time, like with k-means, we will have to pick \(k\) – it’s a hyperparameter of the algorithm.

Figure 10.5 shows an example of the effect. Which result looks more correct? It can be hard to say! Using higher k we get more clusters, and with more clusters we can achieve lower within-cluster variance – the k-means objective will never increase, and will typically strictly decrease as we increase k. Eventually, we can increase k to equal the total number of datapoints, so that each datapoint is assigned to its own cluster. Then the k-means objective is zero, but the clustering reveals nothing. Clearly, then, we cannot use the k-means objective itself to choose the best value for k. In Section 10.3.3, we will discuss some ways of evaluating the success of clustering beyond its ability to minimize the k-means objective, and it’s with these sorts of methods that we might decide on a proper value of k.

Alternatively, you may be wondering: why bother picking a single k? Wouldn’t it be nice to reveal a hierarchy of clusterings of our data, showing both coarse and fine groupings? Indeed hierarchical clustering is another important class of clustering algorithms, beyond k-means. These methods can be useful for discovering tree-like structure in data, and they work a bit like this: initially a coarse split/clustering of the data is applied at the root of the tree, and then as we descend the tree we split and cluster the data in ever more fine-grained ways. A prototypical example of hierarchical clustering is to discover a taxonomy of life, where creatures may be grouped at multiple granularities, from species to families to kingdoms. You may find a suite of clustering algorithms in SKLEARN’s cluster module.

10.3.2.0.0.5 k-means in feature space

Clustering algorithms group data based on a notion of similarity, and thus we need to define a distance metric between datapoints. This notion will also be useful in other machine learning approaches, such as nearest-neighbor methods that we see in Section 10.1. In k-means and other methods, our choice of distance metric can have a big impact on the results we will find.

Our k-means algorithm uses the Euclidean distance, i.e., \(\left\Vert x^{(i)} - \mu^{(j)} \right\Vert\), with a loss function that is the square of this distance. We can modify k-means to use different distance metrics, but a more common trick is to stick with Euclidean distance but measured in a feature space. Just like we did for regression and classification problems, we can define a feature map from the data to a nicer feature representation, \(\phi(x)\), and then apply k-means to cluster the data in the feature space.

As a simple example, suppose we have two-dimensional data that is very stretched out in the first dimension and has less dynamic range in the second dimension. Then we may want to scale the dimensions so that each has similar dynamic range, prior to clustering. We could use standardization, like we did in Chapter 5.

If we want to cluster more complex data, like images, music, chemical compounds, etc., then we will usually need more sophisticated feature representations. One common practice these days is to use feature representations learned with a neural network. For example, we can use an autoencoder to compress images into feature vectors, then cluster those feature vectors.

10.3.3 How to evaluate clustering algorithms

One of the hardest aspects of clustering is knowing how to evaluate it. This is actually a big issue for all unsupervised learning methods, since we are just looking for patterns in the data, rather than explicitly trying to predict target values (which was the case with supervised learning).

Remember, evaluation metrics are not the same as loss functions, so we can’t just measure success by looking at the k-means loss. In prediction problems, it is critical that the evaluation is on a held-out test set, while the loss is computed over training data. If we evaluate on training data we cannot detect overfitting. Something similar is going on with the example in Section 10.3.2.0.0.4 where setting k to be too large can precisely “fit” the data (minimize the loss), but yields no general insight.

One way to evaluate our clusters is to look at the consistency with which they are found when we run on different subsamples of our training data, or with different hyperparameters of our clustering algorithm (e.g., initializations). For example, if running on several bootstrapped samples (random subsets of our data) results in very different clusters, it should call into question the validity of any of the individual results.

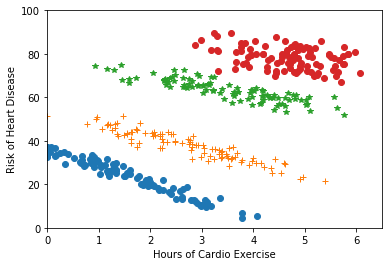

If we have some notion of what ground truth clusters should be, e.g., a few data points that we know should be in the same cluster, then we can measure whether or not our discovered clusters group these examples correctly.

Clustering is often used for visualization and interpretability, to make it easier for humans to understand the data. Here, human judgment may guide the choice of clustering algorithm. More quantitatively, discovered clusters may be used as input to downstream tasks. For example, as we saw in the lab, we may fit a different regression function on the data within each cluster. Figure 10.6 gives an example where this might be useful. In cases like this, the success of a clustering algorithm can be indirectly measured based on the success of the downstream application (e.g., does it make the downstream predictions more accurate).